We recently started our streaming cycle with our discussion on verbs in game design and picked remasters & remakes as our next topic. At this point, every video game enthusiast has probably bought and played one or more remade or remastered games. But what makes them so successful and why do we keep visiting games from the past over and over again? You can check out the whole discussion, as well as us playing Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition here!

We’re currently streaming every two weeks on Mondays 4 pm CEST on our twitch.tv channel.

Remakes & Remasters

What’s your favorite remake or remaster?

Jens: My favorite remaster is the Splinter Cell trilogy just because I love the game so much. Not because it’s a great remaster or anything. It’s just been so much fun to be able to play the game on PlayStation 3.

Jannik: I don’t really play many remasters. I don’t think I can even think of more than one I’ve played. And that’s the Crash Bandicoot trilogy, the insane trilogy remaster when that came out. I played it to 100%. But that’s also mostly because I loved the original games that much. Other than that, I tend to play vintage games instead, if I can.

Ines: Interesting to see that we all just replay games of our childhood. My favorite remake is the remake of the Pokemon series. And that’s also because it’s just the base game, which I already love with pretty graphics and some quality of life improvements. So yeah, it’s not something that I’ve originally played as a remake or a remaster, but it’s something I’ve had played before already.

Why are so many remasters being made? And why do we like them? Why do we want them? Why do we buy them?

Jannik: Most remakes and remasters seem to be glorified ports, existing primarily to keep up with the most current console release cycle. While many older games can still be played on PC today, every new console cycle makes it harder to replay older console games. This might be one of the main reasons to remaster games: to make them accessible to people who were not able to play them when they came out.

Jens: It makes a lot of sense to do it because it’s not as much work as developing a new game from scratch. Some big companies have these super successful older games in their portfolios, just gathering dust. So of course it makes sense to use the assets that they created 10 or 20 years ago, to again, make money and maybe fund the development of the bigger games of the new series that they are developing.

Ines: I just don’t want to lose any games. I want to keep them with me. I want to take them with me. And so I buy them again and again for each new platform.

So what do you think is the most important target group for remakes and remasters? Is it mainly people who played the game before and want to keep it, or is it people who didn’t have the original console and might want to play the game now?

Jens: A good mix of both. When a new part of a game series comes out (for example a new God of War), you might want to play or the old God of War titles to prepare yourself. Using remakes and remasters is a good way to enter a long-standing game series. But I personally just want to relive these games that I’ve played many years ago. So yeah, I guess it’s a mix of both.

Jannik: There might also be a different motivation depending on who you ask at the development studio. I think most of the developers are probably in it to recreate the game for old fans. You often see how much love is poured into keeping old details in the games, enhancing them. It’s probably a decision from stakeholders to actually start a project – just to squeeze out all the IP still has to offer.

Jens: It also bridges a time gap. Yesterday I read that a new remaster of Zelda: Skyward Sword has been released. The article also talked about the fact that it’s mainly there for bridging the gap until Breath of the Wild 2 comes out. And it makes sense – we want to keep our fans happy and give them something while they’re waiting for the new game. And to keep the Zelda name in the news.

Are technical limitations a part of the old games? Do we even want all of the games from our childhood to look better now, or exactly the same?

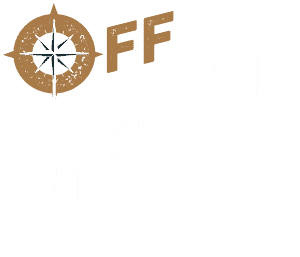

Jannik: I feel that that’s the danger with remastering or remaking games. Fans can sometimes be scared that the games they love might somehow be ruined. And I think that many successful older games pushed technical limits in some way or another. They did something that was not really possible on those consoles, or at least people didn’t think it possible. Let’s look at this direct comparison from the PS1 and the PS4 version of the Crash Bandicoot games. They both look great. but part of what made the original Crash games so great were the limitations the developers had to work around. For example, bone animations weren’t possible at the time. So the developers just animated single vertices, which made Crash have a really insane range of expressions. This is one of the things where I think that’s something we lost in a remaster. It’s a great game, it still plays very well, I loved it, but in comparison to the new one, the old one felt much more memorable, because it kept pushing boundaries.

Ines: That also shows how important it is to stay connected to your audience. And to know what it is that people love about your games, and what it is that they wouldn’t want to miss. You don’t want to make anyone unhappy just because you don’t know and respect what they loved about these classic games.

Jens: Sometimes these technical limitations fostered creativity, or even influenced the game design. Silent Hill 2 comes to mind, where they had very limited hardware to work on. In order to still be able to render quite sophisticated 3D models, they reduced the draw distance and implemented a strong fog effect – which made the game much scarier to play. When they released the HD remaster years later these technical limitations were gone, and somebody decided to increase the draw and fog distance — effectively making the game less scary, because now you could see enemies coming from far away. So when we create remasters and remakes we need to stay faithful to how the classic game felt, even if that means that technical limitations have to be emulated.

Jannik: I think most of the great games of older times on older platforms were always defined by the platform. And nowadays, most of that magic is just lost, because we can do whatever we want in our games.

Ines: And also, when we think about games from our childhood or from earlier in our life, what we remember is not just the story and the characters, but it’s also it is the graphics and the audio of the game.

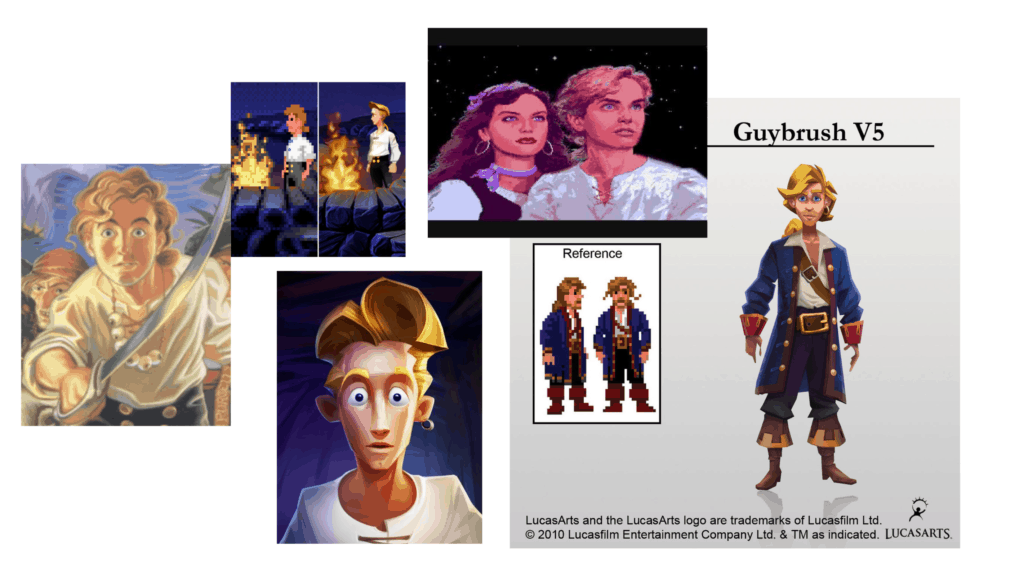

Jens: So in a remaster you kind of keep the old files and just make it work on a newer console, while a remake is kind of created from scratch in a much higher definition. And then suddenly you have to answer a lot of questions like: how would this graphic look in HD? Suddenly we have all these pixels, how do we fill them with information based on the few pixels that existed in the original game? I recently read an interview with Tim Schafer about the Monkey Island remake, and he said that he was a bit surprised by the length of the hair of the main character Guybrush Threepwood. Back then there was a lot of controversy just around some details in the remasters being a bit different than people imagined them to be based on the old games. But when you develop a remake, you have to somehow fill in these gaps. You have to somehow draw his hair in high definition, but that’s very difficult to get it right for everybody. Maybe even impossible.

Are there too many remasters nowadays?

Jannik: That question crept into my mind a few months ago when I heard that there was going to be a Life is Strange – Remastered Collection. I felt like I lost track of time. I kept thinking: “Wait, that game only came out like three years ago? Maybe five years ago? What’s happening? Why are they remaking it already? I can still play it on Steam!”. When I think of remasters I think of games that came out 15 or 20 years ago.

Ines: It’s interesting to see how for some series, e.g. the Pokemon series, we already know and expect there is going to be a remake reasonably soon. So we’re not just looking forward to the new games – we’re already expecting these remakes of old games as well.

Jens: I think we also reaching an era of gaming where many games are simply still available to play. Like Jannik just said: he can go to his Steam library and play Life is Strange. Games don’t usually fall out of your Steam library. They stay there and you can still play them even if you bought them 10 years ago. Most of the newer consoles are also backward compatible again. I can use my PS5 to play PS4 games – so I don’t really need a remastered version, do I? Maybe the need for remasters is decreasing that way?

Ines: I’m also wondering if the era of remakes is going to end because graphics have improved so much. For example, when I look at the original Final Fantasy 7, it looks really, really blocky. It was the first 3D game in the series and although I like the series, I’ve never played FF7 because I just couldn’t get comfortable with the looks. But games that come out these days are already so realistic and pretty, that maybe we don’t need to upgrade their looks to make them playable again?

Jens: If people buy it, It’s worth making it. I’ve seen many people spending money on upgrading their PS4 games to a PS5 version, even though they could play both versions on PS5. The upgraded version simply has a better resolution and more fps – and still, people are paying for the upgrades. I am guilty of this as well: I could just go to my living room and boot up my old GameCube, which is still standing there, and play some classic Splinter Cell. Or the PS3. But somehow I want to play these games on my shiny new PlayStation 5.

Jannik: That shines a light on how transformative cloud gaming services can be. Decoupling games from hardware. When we do that, a big part of why we remake games just fades away.

Jens: I think people don’t really necessarily want the games to be exactly as they were 20 years ago, but they want them to be like they remember them, which is a big difference. For example, when we think about Point and Click Adventure games, we mostly remember the feeling of solving the puzzles and laughing at the jokes – and not the feeling of being stuck on a puzzle for hours. Or days. And that brings me to one other thing from the article about The Secret of Monkey Island that I read. Ron Gilbert, one of the original developers of Monkey Island, and also one of the developers of Thimbleweed Park (which we played last time), talks about the fact that they included a hint system in the remake, which did not exist in the original game. They only added that feature to the remastered version to make the game more accessible for a new audience. How can we keep the original spirit of how these classic games feel, while also making them more playable for a modern audience, which might be used to a certain quality of life improvements.

Ines: I just noticed how emotional it is for me to talk about this because I want to keep my games forever. And I want to be able to play them forever.

Join us for our next stream!

We’re streaming our live discussions every second Monday at 4pm CEST on Twitch, so join us there and have a chat with us!

If you have ideas and inspirations on what topics you’d like to hear us discuss and what games we should play during our streams, let us know over on our discord server!

We’re also currently working on our story-driven adventure “The Cost of Recovery”. It’ll put you into the shoes of different family members when one of them suffers a stroke. What sacrifices are you willing to make to keep your loved ones close? Check out the game on Steam by clicking on the banner below!