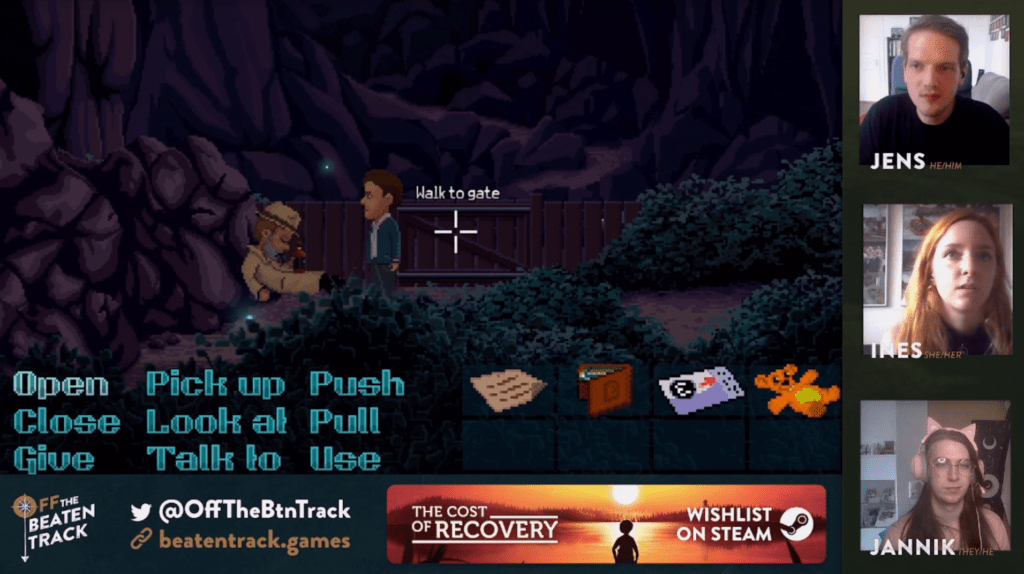

After streaming all of the Adventure Jam 2021 games, we noticed that verbs are an integral part of the design of adventure games, and in game design in general. That’s why we decided to make talk about verbs in games and then go on to play Thimbleweed Park, which uses a very traditional verb-based interaction system. You can check out the discussion here and watch us playing Thimbleweed Park here!

We’re currently streaming every two weeks on mondays 4pm CEST on our twitch.tv channel.

For your convenience, you can also just listen to our rambling as a podcast here:

Verbs in Game Design

Verbs are a super important part of game design. When you just think about “What do I do in a game?”, it’s usually a verb that comes to mind. For example, when you think about Super Mario, you think about running and jumping. And suddenly you have the jump-and-run genre. Verbs are the thing that defines the core mechanics, and by defining your verbs you really define the kind of game you’re going to make. When I just say “imagine a game where you drive and steal and shoot.” you’re probably thinking of Grand Theft Auto. And when I talk about a game where you just run and hide, it might already feel a bit like a horror game. In some games, particularly Metroidvania games, unlocking new verbs is a key part of progression through the game. For example, players might unlock the jump or swim mechanics and then be able to reach new places in the world.

Verbs really define the experience that the players have in the games that we create.

Jens

These verbs can even build onto each other, creating new possibilities and unexpected behaviors, oftentimes called dynamics (based on the “mechanics, dynamics, aesthetics” game design paradigm). Within this paradigm, the mechanics are defined by our verbs. Dynamics are building on top of the mechanics — most of the time when they stack onto each other or are used in combination. We see that a lot in Zelda games, particularly in the newest Breath of the Wild game, which offers a broad set of mechanics, and then you can combine them to create a huge amount of new dynamics to solve situations in many creative ways. For example, the simple verbs hit, freeze and climb can be combined to traverse the world like flying on a rocket launcher.

That’s something that doesn’t really happen in adventure games. In adventure games, the verbs that are presented on the screen are not the core mechanics – they are just parts of a puzzle. Even from the name of the genre “point and click”, it’s already clear that the main mechanic is not defined by the verbs on screen, but by pointing and clicking. The main mechanic is choosing one thing and then clicking on the other thing, essentialy combining verbs with other items on screen. But these verbs are rarely interacting with each other, forming dynamics or other unexpected situtations — which would be a very interesting thing to do in an adventure game.

Verbs in Adventure Games

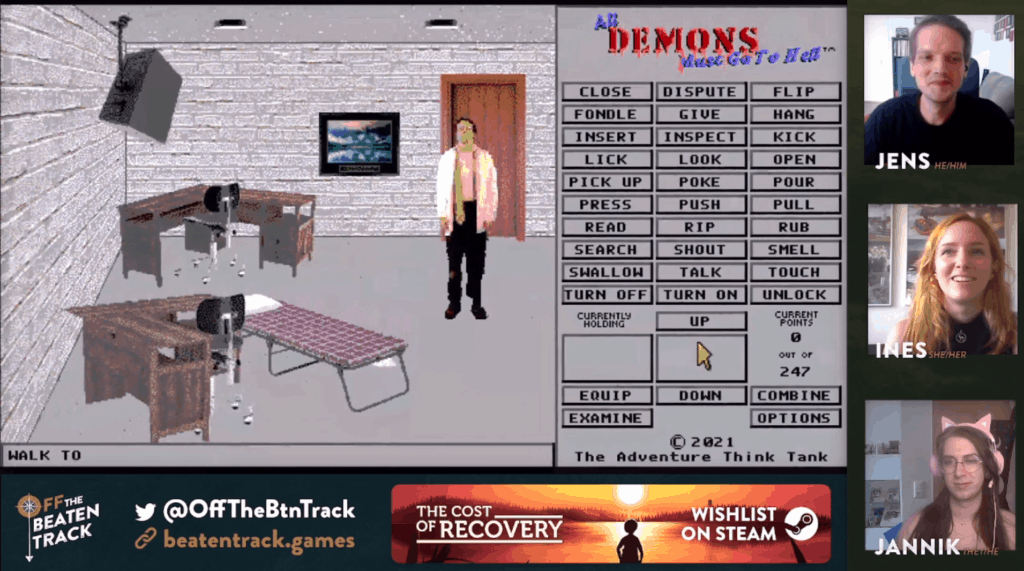

Across the Adventure Jam 2021 entries there were a lot of games that used verbs differently – as part of the UI like in ‘classic’ Point and Click games, or hidden away in contextual interactions or as part of their core loop. One game that stood out to us was “All Demons Must Go To Hell“, which offers more than 30 (!) verbs to choose from for every interaction and basically made fun of the amount of verbs in classic adventure games. Some of them are a bit crazy like “lick”, “dispute” or “pour”.

The gamejam game managed to keep the response to most of these verbs interesting and meaningful. It’s a game that is designed to be frustrating, and that really shows us “Hey, this is how not to use verbs!”. Oftentimes in adventure games, if you try out different verbs on different interactions, you’re presented with generic responses like “I can’t do that”, or “I shouldn’t do that” – which quickly breaks immersion, diminishes fun and causes players to simply try random things until they find a the correct solution.

That’s a problem, because it means that in many adventure games we can only use our verbs, which are supposed to be our core mechanics, in the predefined “correct” ways the designers intended. That’s like only allowing Super Mario to jump in those spots where the designers decided that it would make sense to jump. The input and intent of the players are no longer respected. This disconnect might be one of the bigger things that adventure games have to tackle – how they really make sure that all these verbs are really core mechanics, and that we get direct and good feedback for our inputs and intentions at all times.

Some adventure games try to remedy this situation by offering contextual verbs. In this case, a pre-defined verb is chosen for more obvious interactions – for example, when clicking on a closed door, the “open” verb is automatically selected. This takes out a lot of the guesswork and is a huge quality of life improvement – there even are some remakes of old adventure games which offer these contextual interactions even though their original version did not (e.g. The Secret of Monkey Island). That’s a good thing, because then the game becomes less about guessing what the designers intended for the players to do, and more about simply interacting with the world in meaningful ways. But on the other hand, it also waters down the experience of classic adventure games and is not very popular amongs die-hard fans of the genre. By making the game and puzzles easier, the feeling of accomplishment is diminished as well.

The feeling of accomplishment

When we talk about game design, we often talk about quality of life improvements, streamlining things and taking out unneccessary complexity. However, by watering down the complexity of games it’s harder to achieve a feeling of achievement. The bigger the obstacle, the harder it is to get there, the bigger the feeling of success. At one point I tried to kill a boss in Bloodborne for two weeks, and I failed and failed and failed. But when I killed it, it was a big, big success for me. But for that feeling of success, you need to overcome an obstacle.

That feeling of success is a tricky thing, because you kind of need an obstacle.

Jens

However, it also depends on what the obstacles are the game presents to me. “Which verbs should I click on to open this door?” might not be a good obstacle to present the player with. Ideally, obstacles should relate to the core mechanic, and not to guessing what the designer’s intended – as players, we want to feel clever and skillfull when we solve a puzzle. Puzzles need to make us feel smart when we solve them, and that usually comes from a clever and unexpected use of the core mechanics of the game.

The feeling of accomplishment instantly goes away when players have to look up the solution of a puzzle – which happens much more quickly these days, because it’s so easy to do. While players were fine with being stuck on a particular puzzle for hours (or even days) 20 years ago, their patience is much more slim now that the solution to every puzzle is just a quick google search away and their steam libraries are overflowing with other games they want to play.

Some modern adventure games include hint systems, trying the keep the players from directly looking up the solutions when they might be stuck. Some games even offer multiple different hints for each puzzle which increase in how obvious they are. That way, players still feel a sense of accomplishment when solving the puzzle – because they got hints and then figured it out themselves, instead of being fed with the direct solution.

The case of “examine”

Another game from the Adventure Jam 2021 lineup that sparked a discussion was “Thinker“. Here we discussed the importance of the “look at” function in adventure games. One one occasion there was a red button on the wall, but we could not interact with it because the game required us to “examine” it first – something we didn’t think would be a requirement at any point in the game.

If I see a big red button, I know what it means. I know what to do with a big red button. I’m going to push it. There’s nothing complicated about the button I need to find out first. It’s a big red button, I will left click it, I will push it.

Jannik

In many of the adventure games we played, when we actually had to use examine as a verb, we didn’t even think about it and needed hints from the chat. It didn’t occur to us, because it wasn’t a required part of the game before, or it wasn’t clearly communicated to us.Jannik noted that for him, as a player, he’s expecting right click to be “I want to find out more about object, I want to have world lore, I want to get into the story” – but not a functional, required part of the game. One solution might be clearly communicating that examining is required, for example as a hint the player character would say when players try to interact without examining first. Or by communicating early in the game that some puzzles require interacting as part of puzzle solving – maybe as part of the tutorial. Once the player has been taught that examining is a vital part of the game, they will keep it in the back of their head as a possible solution to some puzzles. But it has to be taught at some point; it was not obvious to us that this would be the case.

Join us for our next stream!

We’re streaming our live discussions every second Monday at 4pm CEST on Twitch, so join us there and have a chat with us!

If you have ideas and inspirations on what topics you’d like to hear us discuss and what games we should play during our streams, let us know over on our discord server!

We’re also currently working on our story-driven adventure “The Cost of Recovery”. It’ll put you into the shoes of different family members when one of them suffers a stroke. What sacrifices are you willing to make to keep your loved ones close? Check out the game on Steam by clicking on the banner below!